Aug 05, 2024

Close to home: As you approach the age of needing residential care, here are your options and the price tag

Posted on:Jul 31, 2024

One big challenge of planning your retirement is trying to figure out how much you might need to pay for care in a residential setting late in life.

No one can know reliably in advance what later health issues will arise. And the network of in-home care, retirement homes and long-term care homes is a patchwork mix of public and private services, so navigating it can be tricky.

But having a general understanding of your residential care options and what they cost is a good starting point.

The key for middle-class Canadians of average means is to make the most use of government-supported care where appropriate and available, but then supplement it judiciously with care paid for out of your own pocket.

Of course, wealthy Canadians can afford more expensive care options while lower-income seniors are more dependent on limited government services.

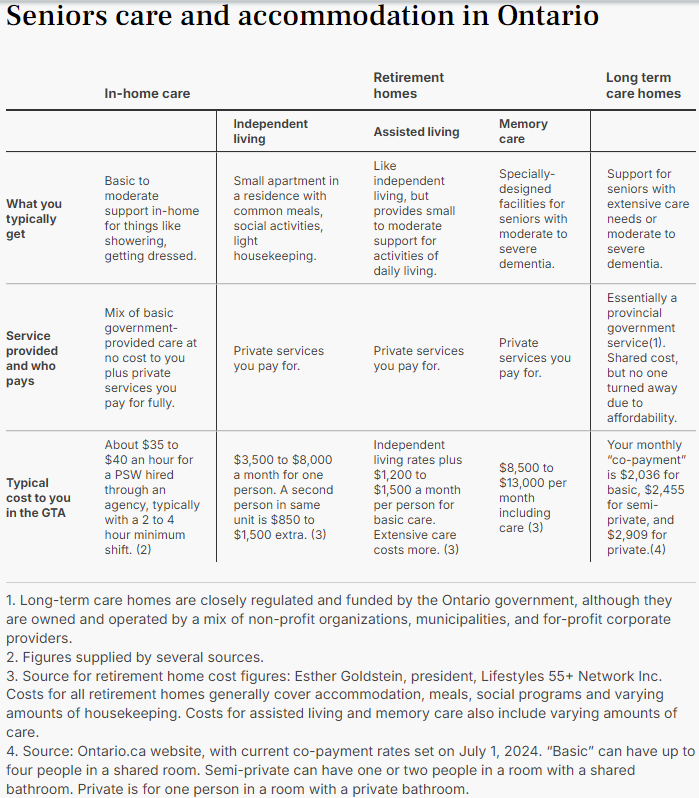

What follows is an overview of the three major forms of care provided in a residential setting: mixed private and government in-home care; private retirement homes; and government long-term care homes. The attached table provides typical costs that you can expect to pay for these services in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA).

Coming to grips with the ‘continuum of care’

The three services support a spectrum of care needs.

“People have to understand the continuum of care, what the options are along the way,” says Karen Henderson, independent planning specialist with the Long Term Care Planning Network.

It starts with in-home care, which is a mixture of limited government services and private services you pay for. Used sensibly, home care can often extend your ability to thrive in the traditional family home for longer.

At the other end of the spectrum, government long-term care homes provide intensive physical assistance and dementia care for those needing a lot of help.

Residents cover some of the costs with a “co-payment,” although no one is turned away because of affordability.

In the middle are retirement homes, which you pay for entirely yourself. These homes are generally well-suited to seniors who need limited help with the activities of daily living but who are still relatively active.

One anomaly is that long-term care homes generally provide more extensive care than retirement homes, but heavy government subsidies make them cheaper in terms of what you pay.

Eligibility and access to government in-home care and long-term care homes is determined by care co-ordinators with Ontario Health atHome (OHaH), formerly Home and Community Care Support Services. Of course, government-supported care is subject to enormous demand and limited supply.

Public in-home care is limited

With government in-home care availability, “I would say it’s down to the neediest of the needy,” says Audrey Miller, managing director of Elder Caring, a national agency which helps families navigate the care system.

Miller says that OHaH tends to prioritize activities like: help with bathing once or twice a week for seniors at high risk of falls; palliative care; and short-term help with things like wound care or physiotherapy for seniors transitioning home from hospital.

If you can’t get government in-home care to provide the help you’re looking for, it might make sense to pay for a modest amount of in-home care out of your pocket. But it costs about $35 to $40 an hour for a visit from a personal support worker (with a two- to four-hour minimum). So if you want frequent visits, these services become unaffordable for many seniors of average means.

But in addition, as seniors become less mobile, many find staying in the home to be isolating and not ideal for staying social and active.

So as you need more help, some combination of needs and finances often determines that support is best provided in another setting.

Retirement homes provide a social setting

Retirement homes are best suited to seniors looking for some help with daily living in a social setting with a lot of activities.

“Retirement homes provide seniors with a social environment,” says Esther Goldstein, president of Lifestyles 55+ Network, which provides listings of seniors accommodation and services at SeniorCareAccess.com.

“These seniors have social activities, they have nutritious meals provided, basic housekeeping services, and many have medications given to them on a proper schedule,” says Goldstein. “They can often live healthier for longer than if they languish in their family home beyond the point where that makes sense.”

The typical cost of a retirement home is around $3,500 to $8,000 a month for “independent living,” which usually covers rent for your own apartment, meals, light housekeeping, and social activities, says Goldstein. With “assisted living” and “memory care,” you pay more to add varying amounts of care.

While that sounds like a lot, realize that for seniors at this stage of aging, their retirement home payment typically comprises almost all their monthly budget. So costs at the lower end are within reach of many middle-class Canadians of average means — especially those that sell a family home when they move to a retirement home.

Of course, renters without sizable nest eggs or good pensions might not be able afford them, forcing them to continue living on their own or move to a long-term care facility when those options aren’t optimal.

“Those are the people falling between the cracks,” says Goldstein.

But also, as care needs increase, costs often pass the threshold of affordability for the middle class as well. If you need a lot of physical assistance in assisted living or help with severe dementia in a memory care facility, costs can sometimes reach $10,000 a month or more.

In addition, the activities in retirement homes are well-suited to relatively active seniors. But as seniors become less active, that benefit becomes less relevant.

And retirement homes often don’t offer many of the intensive full-time nursing services that long-term care homes are mandated to provide, says Miller, such as regularly turning immobile seniors in bed to avoid bedsores, or employing a mechanical lift to transfer those seniors from bed to chair.

So at some point, some combination of increasing care needs and affordability may compel a move to a government long-term care facility.

Supplementing support in long-term care homes

Whether long-term care facilities meet expectations for care or not is a fraught topic with long wait-lists making it a challenge to just getting in the door.

Care quality varies from home to home, so it’s hard to generalize. But it’s fair to say long-term care is designed to provide essential, medically-correct care, but finances and staffing are tight. So they don’t generally provide much in the way of activities and support that isn’t absolutely required.

For middle class families that have some money to draw on but aren’t wealthy, one good strategy is to embrace the public long-term care system if a high level of care is required, but then spend judiciously out of your own pocket to supplement it.

If you can afford it, it usually makes sense to pay up for a semi-private or private room, which is more expensive than sharing a basic room with up to four people.

Also, you can pay to bring in a companion or other extra caregiver to provide extra engagement and stimulation. That’s especially helpful if family isn’t available to visit as often as they would like.

“If you can afford it, it’s always a good idea to bring in a companion to supplement care,” says Henderson.

“I’ve had many families who have been very happy with long-term care,” says Miller. “And being able to supplement privately can take the load off a family caregiver big time.”